- About EDS

- Navigating Healthcare

- Mental & Social Health

- Programs

- Resources

- Patient Stories

- Research Alerts

Shared with permission from EDSAwareness.com

“The 2017 [hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome diagnostic] criteria were introduced to improve diagnostic specificity but have faced criticism for being too stringent and failing to adequately capture the multisystemic involvement of hEDS,” states a paper titled “Looking back and beyond the 2017 diagnostic criteria for hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: A retrospective cross-sectional study from an Italian reference center” by Marco Ritelli, Nicola Chiarelli, et al. published in in the American Journal of Medical Genetics last fall (made available online in January 2024). After the collection and analysis of data, the researchers advocate for “a revision of the 2017 diagnostic criteria. By broadening criteria, it will be possible to more accurately capture the diverse range of symptoms and manifestations present within the hEDS (hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome) and HSD (hypermobility spectrum disorder) spectrum, ultimately leading to improved diagnostic accuracy and enhanced patient care.”

Attempts to classify the Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes (EDS) began in the late 1960s, and a nosology (a word that refers to a list or classification of a disease) was published in 1988. It defined nine subcategories of EDS and was written, in part, by Peter Beighton, the same person who developed the Beighton hypermobility scale. The paper is called “International Nosology of Heritable Disorders of Connective Tissue, Berlin, 1986.” Sometimes called the Berlin nosology, this paper describes the symptoms and signs associated with a number of connective tissue disorders, including EDS.

Nine types of EDS were defined. While the EDS types could be referred to by their numbers, they also had names like “Gravis type,” “Mitis type,” “Hypermobile type,” “Vascular”—with four subtypes—the “X-linked type,” “Ocular-scoliotic type,” and more. “Cardinal manifestations” were listed, some being a general symptom for all types of EDS, such as “skin–hyperextensible with soft, velvety, doughy texture; dystrophic scarring; easy bruisability, joint hypermobility, and connective tissue fragility” (Beighton et. al., 1988).

Other manifestations were specific to the various types: “cardinal manifestations in a severe degree” was a manifestation for EDS 1; “marked articular hypermobility,” among other manifestations for EDS 3; “variable stigmata,” “vascular rupture,” and “colonic perforation,” among other manifestations for EDS 4; manifestations for EDS 8 included “aggressive periodontitis, gingival recession, and early tooth loss” (Beighton et al. 1988). In these descriptions, we can see the shadows of classical EDS, hypermobile EDS, vascular EDS, and periodontal EDS.

In 1997, a group of medical professionals met in Villefranche-sur-Mer, a town on the French Riviera, to revise and simplify the EDS descriptions. Again, Beighton was present, and he says in the 1998 paper titled “Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes: Revised Nosology, Villefranche, 1997,” “we propose new, simplified classifications of EDS into six major types[…] For each type, we defined major and minor diagnostic criteria.” The six new types were called Classical type, Hypermobile type, Vascular type, Kyphoscoliosis type, Arthrochalasia type, Dermatosparaxis type, and Other forms. Other forms included X-linked EDS, Periodontitis EDS, Fibronectin-deficient EDS, Familial hypermobility syndrome, Progeroid EDS, and Unspecified forms (Beighton et al. 1998). This nosology also included, when known, how the type was inherited (autosomal dominant or recessive) and the gene or type of collagen that was affected to cause that particular type of EDS. It was assumed that “most, if not all, of these types of EDS were a consequence of alterations in fibrillar collagen genes or in genes that encoded collagen modifiers” (Malfait et al. 2017), and that understanding led to the reduction in the number of types of EDS.

Twenty years later, in 2017, an accumulation of medical and scientific research, especially into genetics, the human genome, and genetically caused diseases, begged for a revision of the EDS nosology once again. “[A] whole spectrum of novel EDS subtypes has been described, and with the advent of next-generation [genetic] sequencing facilities, mutations have been identified in an array of new genes that are not always, at first sight, involved in collagen biosynthesis and/or structure,” Malfait et al. explain. It was time for a literature review and, based on that review, a revised set of EDS classifications. The new nosology (sometimes called the New York criteria or just the “2017 criteria”) includes the 13 subtypes we know of today, with various genetic information, new names and abbreviations (including ones like classical-like EDS or clEDS and cardiac-valvular EDS or cvEDS), major and minor criteria for clinical diagnosis, as well as the molecular basis for genetic diagnosis.

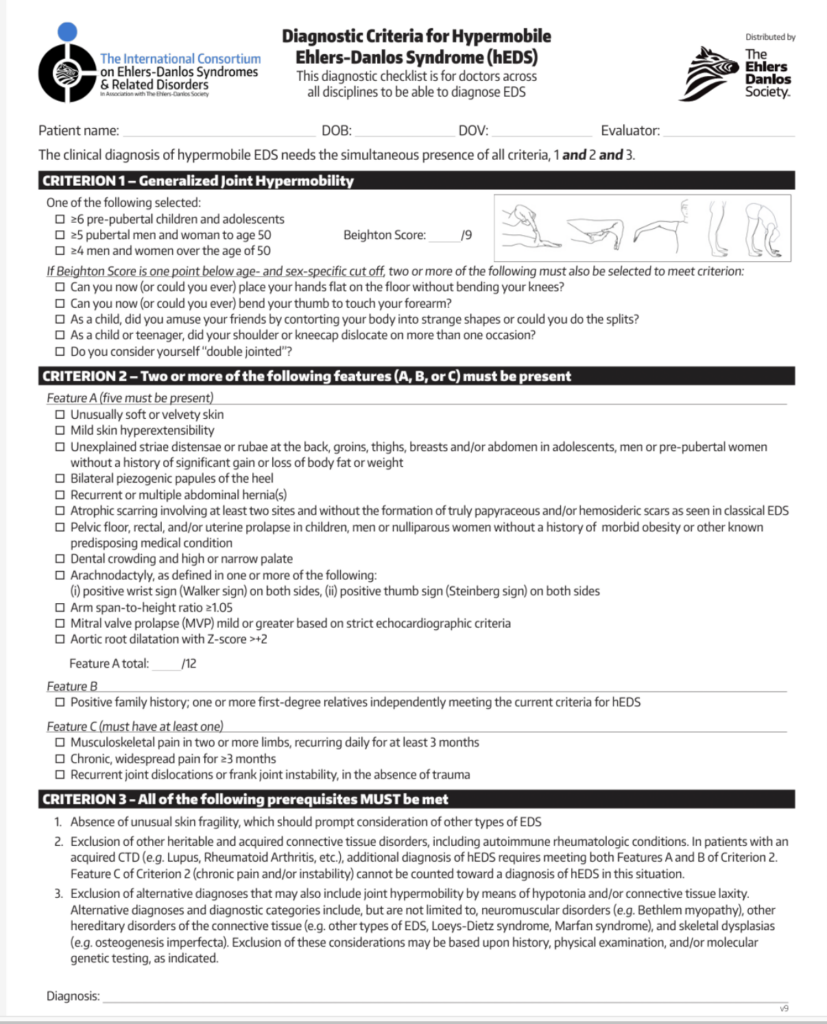

That is, except for hypermobile EDS. The authors lament the lack of genetic information surrounding hEDS and introduce the diagnostic checklist, which contains three criteria that must be met to secure a clinical diagnosis for hEDS (Malfait et al. 2017). These diagnostic criteria are important, as they are the only factor deciding who has hEDS and who doesn’t. According to the authors of the Italian study, much of the 2017 diagnostic criteria for hEDS and the diagnostic criteria for HSD are vague and overlapping. In many cases, if a person doesn’t meet the criteria for hEDS, HSD is diagnosed as a default. This is troublesome as some healthcare systems don’t recognize HSD as a diagnosis, and insurance may, therefore, not provide reimbursement for care (Ritelli et al., 2023).

This has also led to the question of how prevalent hEDS actually is. The Ehlers-Danlos Society lists the hEDS prevalence at 1 in 3,000 to 1 in 5,100, making it a rare illness. A rare or orphan illness is defined as a condition that affects fewer than 200,000 people in the United States and fewer than 1 in 2000 people in Europe. In discussing disease prevalence, the higher the second number in “1 of XXX”, the less the condition occurs. They also say that 90% of EDS cases are hEDS cases. (Information retrieved from The Ehlers-Danlos Society in March 2024.) Other sources, such as a paper by Demmler et. al. in 2019, indicate a prevalence of 1 in 500 people in Wales, which would mean hEDS is not rare at all. The NIH database, All of Us, estimates the prevalence of hEDS at 1 in 300 (Ritelli et al, 2023). To put that in perspective, the population of the United States was 331.9 million people in 2021. If the Ehlers-Danlos Society is correct, that would mean there are approximately 65,000 people with hEDS in the US. If the All of Us database is correct, there are over 1.1 million people with hEDS in the US. That’s a pretty big difference. Having defined criteria that can adequately and accurately diagnose patients with hEDS or HSD can mean a huge difference in medical care for over a million people, just in the US. Imagine the world-wide implications.

A screenshot of the 2017 hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome diagnostic checklist from the Ehlers-Danlos Society

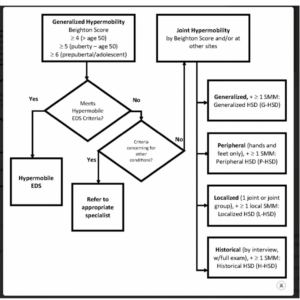

A screenshot of diagnostic criteria based on joint hypermobility for hEDS and HSD (referred to as “Joint Hypermobility” in the image) from Atwell et al. 2021.

The Italian researchers wanted to know if the 2017 diagnostic criteria were effective in a) identifying people who had been diagnosed with hEDS pre-2017; b) if the 2017 diagnostic criteria are enough to differentiate hEDS from HSD; and c) if the 2017 criteria include the major signs and symptoms of hEDS as reflected in a population of patients previously diagnosed with hEDS and HSD.

The researchers did a retrospective study on a cohort of 327 patients from 213 families found at a clinic in Spedali Civili University Hospital in Brescia. All patients were diagnosed as either ht-EDS (hypermobile type-EDS) per the Villefranche criteria (125 [38.23%] of the cohort) or with joint hypermobility syndrome (JHS) according to the Brighton criteria (326 [99.96%]) published in 1998 by Grahame, Bird, and Child.

After identifying the patients in the cohort, the researchers reviewed the patients’ charts and assigned a diagnosis—hEDS or HSD—based on the 2017 criteria, noting which signs and features, if any, the patient had. They also noted the presence or absence of 95 other physical and mental signs or features not present in the 2017 diagnostic criteria. When the researchers had collected their data, they performed statistical and mathematical analyses to determine their various outcomes.

In general, the researchers found that “the current diagnostic criteria [for hEDS] are too stringent to capture all patients with hEDS,” as only about 35% of the patients previously diagnosed with hEDS (prior to 2017) met the new criteria. The others were classified as having HSD, with men more likely to find themselves with HSD. (Note: none of the patients actually had their diagnosis changed.)

Of the three mandatory criteria in the hEDS diagnostic checklist, the researchers found that the cut-offs associated with criterion one–the measurement of generalized Joint Hypermobility using a Beighton score–was one of the main factors that made a difference between a hEDS diagnosis and a HSD one.

Researchers found problems with the Beighton score (the majority of criterion one), including that it focuses too much on the upper limbs; it only measures movement in one direction; it was not designed for clinical diagnosis (it was designed for screening children for joint hypermobility); and it can fluctuate based on temperature, side of the body measured, clinician practices and training, and more (NIH).

About 40% of the patients in this study did not fulfill criterion two, leading the researchers to call it “excessively stringent.” The main reason for not meeting criterion two was the lack of the signs and symptoms listed in feature A. Five of the 12 signs and symptoms were each only found in 20% or less of the participants and showed no significant difference in frequency between hEDS and HSD. The remaining seven criteria were prevalent in both hEDS and HSD participants, ranging from 45% to 85% each. Additionally, some physical signs varied significantly between sexes and age groups, with no specified method to control for clinician interpretation of signs.(For detailed data about these physical signs, the study includes easy-to-understand graphs. They can be seen in the Results section of the study, under section 3.2 “Diagnostic criteria according to the 2017 EDS nosology” and section 3.4 “Multisystemic manifestations.”)

Feature B: positive family history of hEDS

Of the patients diagnosed with hEDS, 29.20% had this feature, whereas only 16.36% of patients diagnosed with HSD did, making it a significant difference between hEDS and HSD. They observed that in about 50% of the families with more than one family member with hEDS or HSD, both hEDS and HSD were present; not in the same person, but some people in the family had hEDS while others were diagnosed with HSD. Due to these findings, the researchers feel hEDS and HSD should be considered as different places along the spectrum of one condition (Ritelli et al., 2023). The researchers argue that feature B should be given more weight, especially for patients who don’t meet criterion one but still show symptoms of hEDS.

Feature C: other signs

Feature C has three sub-features involving joint dislocation, chronic pain, and musculoskeletal pain. At least one of the features was present in 94.80% of patients in the study, which is enough to meet feature C. The most common feature present in the hEDS and HSD patients was recurrent joint dislocation or frank joint instability in the absence of trauma.

Criterion three has three requirements that must be met: absence of unusual skin fragility, exclusion of other possible heritable and connective tissue conditions, and exclusion of other conditions involving joint hypermobility. All patients in both the hEDS and the HSD groups met this criterion.

As detailed above, the researchers believe that criterion one of the current hEDS diagnostic criteria–the Beighton score and its interpretation–is one of the main reasons many symptomatic patients do not receive a diagnosis of hEDS. They argue that “criterion 1 remains too stringent and limited to identify patients, often highly symptomatic, who do not meet the Beighton score.” They advise using the Beighton score and the 5PQ on all patients, or using a different joint hypermobility assessment tool. The researchers conclude, “[Changing criterion one] is critical in our opinion since the strictness of the 2017 criteria has already caused considerable confusion among researchers, clinicians, and, most importantly, those who live with these conditions.”

The lack of instruction, the potential differences in clinician interpretation and severity, as well as the inclusion of rare symptoms, led the researchers to rewrite feature A in criterion two. The authors suggest expanding feature A and assigning points to different signs and symptoms. These point assignments are based on the other 95 symptoms studied as well as other research into hEDS and HSD.

Two points assigned for:

One point assigned for:

For criterion two, then, women would need to accumulate 14 out of 33 points and men, 13 out of 32, to meet feature A and would need to meet one of the criteria in feature C, which would remain unchanged in their new paradigm. Therefore, the changes they suggest are:

Feature C of criterion two and criterion three would remain the same.

When the researchers applied their suggested revised criteria to the index-case patients in the study, 110 patients met their suggested revised hEDS diagnostic criteria, which is 33 more patients than when the 2017 criteria was applied. Additionally, all 77 patients who were originally diagnosed with the 2017 criteria were also diagnosed when the researchers’ suggested criteria was applied.

Other features such as chronic pain, sleep disturbances, dysautonomia, fatigue, psychological issues, and more are difficult to definitively link to hEDS and can occur in other conditions. The researchers warn, however, that these comorbidities shouldn’t be ignored but instead used to support defined, specific criteria to establish a diagnosis for symptomatic individuals. Larger studies are needed to determine whether there are more comorbidities that can be used to define and diagnose hEDS and HSD.

To be sure, this is an area ripe for further research. While this study provided interesting data and recommendations, it is limited by nationality as well as not examining the patients in person. As many complex, chronic illness patients know, what is recorded in electronic medical records is not always the most up-to-date or accurate information. In addition, features that are present more in older patients than younger patients could reflect the simple realities of an aging body. Differences between the sexes may need to be controlled for when determining whether a feature is part of the criteria or not. Studies with larger and more diverse patient populations will need to be done in order to verify these results.

A 2019 study from Wales, UK, in the British Medical Journal also sought to understand the prevalence of EDS and joint hypermobility syndrome (JHS, now known as HSD). They analyzed the medical records of 6,021 Welsh people diagnosed with EDS and JHS between 1999 and 2017 and found that the prevalence of EDS and JHS is higher than previously thought (10 in 5,000 patients or 1 in 500), and their status as rare diseases should be reconsidered. It should be noted that this study looked at all cases of EDS, not just hEDS, and it combined EDS and JHS into one group.

Published in March 2020, the University of Toronto shared the results of their own retrospective study of the hEDS diagnostic criteria in the American Journal of Medical Genetics. They found, similar to Ritelli et al., that the 2017 hEDS diagnostic criteria is too stringent, as it only identified 15% of the patients (n = 131) diagnosed with hEDS before 2017. They found joint hypermobility in only 46% of the cases, citing primary care providers’ Brighton scores being much higher than those of EDS specialists. They, too, call for a revision of the 2017 hEDS diagnostic criteria.

An abstract in volume 23, issue 44 (March 2022) of Genetics in Medicine: An Official Journal of the AMCG describes a 2022 study done at the University of Miami. They evaluated 108 patients diagnosed with the 2017 hEDS diagnostic criteria, noting the various features and signs of the 2017 criteria as well as nine other features they found commonly in their hEDS patients. They found that out of the 20 features used in the 2017 hEDS diagnostic criteria, only 11 showed up in the majority of their hEDS patients. They also found three features that were present in over ⅔ of their patient cohort that do not appear in the 2017 criteria (flat feet, TMJ disorder, and minor valvular abnormalities). Based on these findings, the researchers feel the criteria should be reevaluated.

In 2023, The Pediatric Working Group of the International Consortium on EDS and HSD published an article suggesting a pediatric framework to assess joint hypermobility.

The researchers in this study worry that until there is more research, more education, and more agreement within the medical and scientific communities, “patients with hEDS and HSD will continue navigating a diagnostic wasteland of uncertainty, disadvantage, and vulnerability.” They say that a more inclusive criteria for hEDS would lead to better access to medical care and resources, a larger study population for finding out more about hEDS and HSD genetics, and the creation of better treatments for both hEDS and HSD. Additionally, there will be fewer patients with a HSD diagnosis that remains undefined and therefore difficult to diagnose and treat. However, the gold-star solution for anyone struggling with hEDS, HSD, and the related diagnostic criteria is a genetic marker (or markers), which still remain frustratingly unknown.

Kate Schultz

March 2024

Copyright © 2025 EDS Joint Effort. All rights reserved.